The changing culture around breastfeeding

There’s a great deal of shame and guilt in not being able to breastfeed your baby.

Out of the 280,359 births in Australia in 2019, approximately 14,000 women have difficulties with breastfeeding. Many parents will have the discussion on whether to follow ‘breast is best’, opt to formula-feed or combine elements of both.

As a first-world country, Australia scores considerably worse in breastfeeding rates compared to less developed countries.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends women to breastfeed from discharge to six months, and up to two years of age “for optimal growth, health and development.”

According to the Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA), 95% of women in Australia attempt to breastfeed their babies during their hospital stay. Yet, by the time they are discharged from hospital, one in four babies will have already been fed artificial baby milk. By the second week, the fully breastfed rate plummets to 66 per cent (a fully-breastfed infant does not receive anything other than breastmilk at least once a day). While the exclusively breastfed infants score much lower.

With a heavy emphasis on breastfeeding rates worldwide, there isn’t enough discussion generated around the reasons why women have struggled with breastfeeding and the importance of education.

We take a look at how access to education and ongoing supports networks affects breastfeeding rates in Victoria, helping to gain an understanding of some of the modern issues that mothers face.

How access to antenatal care affects breastfeeding rates

There’s an unspoken expectation for new parents to attend antenatal classes — to learn how to be a parent — and what to expect when you’re expecting. While these classes would be unheard of a few generations ago, they seem to set either unreasonable expectations or open up parents minds to broader ideas of care.

Meeting parents at a Monash drop-in breastfeeding support centre, one parent says going to classes sets an unrealistic expectation of what breastfeeding is like. The quality of antenatal classes depends on who is delivering it, the types of topics that are covered, and the way the information is presented. Some parents say these classes can set unrealistic expectations of what breastfeeding will be like and instead focuses on the nutritional benefits of breastmilk, rather than what to do when you don’t produce milk.

Women are being told about the “adjustment and investment period” during their first few weeks post-birth. Yet, many mothers continue to ask themselves “why didn’t anyone tell me breastfeeding was so hard?”.

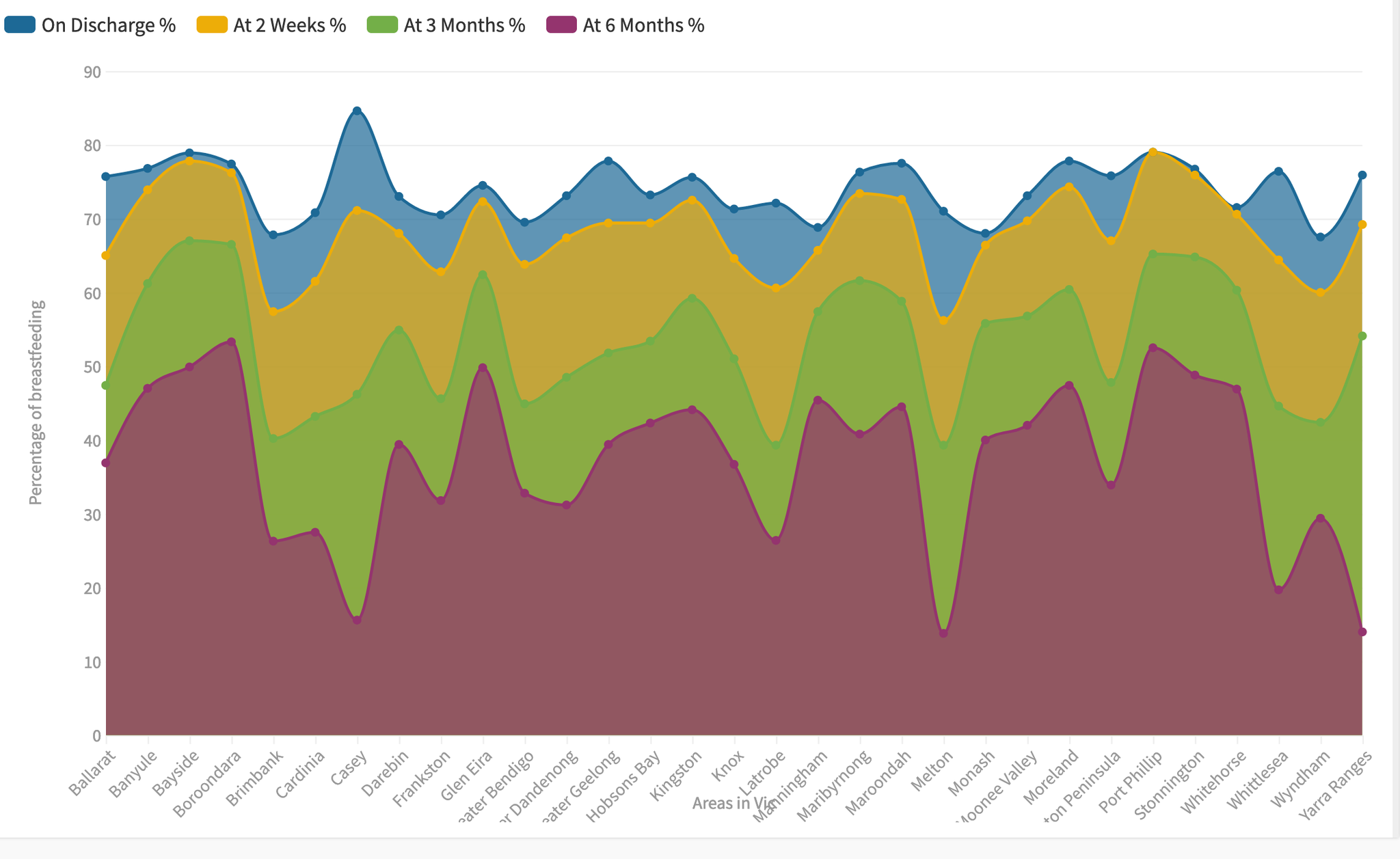

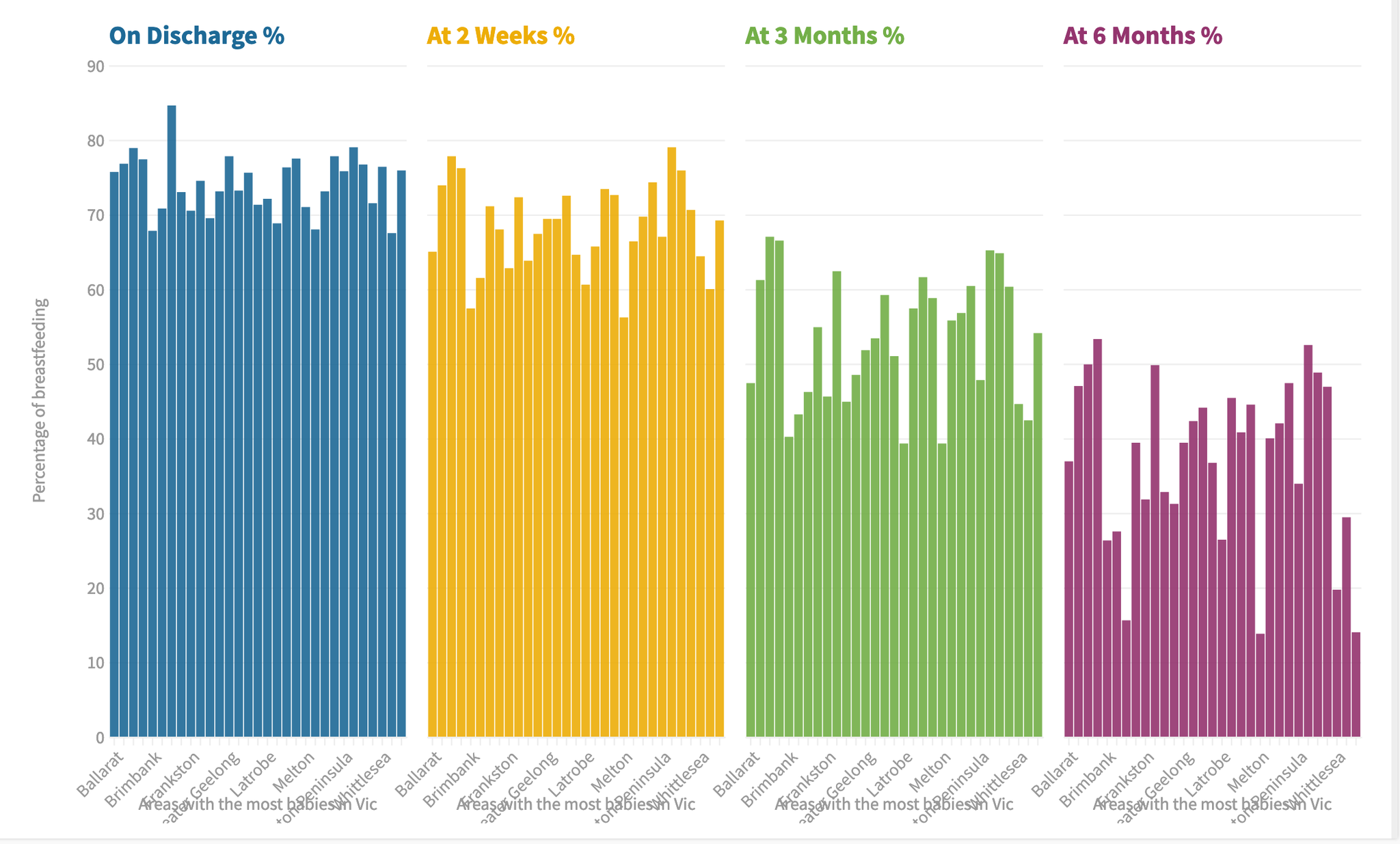

In the Monash City Council, the women had similar rates of breastfeeding from discharge to the two-week mark at 66-68 per cent, with a 10 per cent drop at the three-month mark and another 15 per cent decrease at the six-month mark. This shows having free access to antenatal classes in the public system does make a difference. For other mothers who went to the private hospital system, they found it valuable and “felt the information taught was fair and balanced.” One mother says, attending the classes “helped changed my mindset", as she was initially fixed on strictly breastfeeding. Her son was born with an infection, preventing her from breastfeeding in the first few weeks.

In the demographically wealthier and educated City of Stonnington, the breastfeeding rates from discharge to the second week was 75 per cent, with a similar rate of decline to Monash Council, 65 per cent of women breastfeeding at three months and just under half who continue to breastfeed at six months. This comparison shows a slight improvement in the benefits of higher quality education, but also women living in richer areas are more likely to be aware of the benefits of breastfeeding in the first place.

For families living in low socio-economic areas, this can mean having less access to antenatal services. In the outskirts of the north-western suburbs, areas such as the City of Melton remain isolated, while also being far from support and hospitals. While parents from Melton can self-refer to independent antenatal classes, these classes often come with an out-of-pocket fee. When comparing Melton to Monash who offers free antenatal education, this alone presents a key disadvantage. Melton’s lack of engagement in education is reflected in their poor breastfeeding rates. While their initial discharge rates were average, there were significant drops from the second week and at three months. Only 15 per cent of women continued to breastfeed until six months. The three examples show a strong correlation in breastfeeding rates with access to quality antenatal education, however, the on-going support also has a big impact.

The availability of post-birth support services and support

Mothers emphasise the importance of having continual support, not only for the baby but also for themselves.

Monash Health Lactation Consultant, Ursula Alexander-Smith, says women are “lulled into a false sense of security” within the first few days of giving birth. In a hospital environment, women are supported by midwives and lactation consultants to coach them on how to breastfeed. When families go home, many find they are unable to cope with their “screaming baby” — raising self-doubt and concerns over what issues the infant may be having.

Alexander-Smith emphasises the importance of “understanding your baby (by) the tone of the cry and how you calm them (with) food or a cuddle.”

For one mother she says there’s a great focus on checking up on the infants during their milestones, but there are no check-ups for the mother. This statement is highly concerning, as there are a number of post birthing issues that can prevail in the first six months of care, such as birthing trauma’s, lack of support networks and undetected postnatal depression.

In the book, Guilt-Free Bottle-Feeding, authored by journalist and mother Madeleine Morris — the breastfeeding culture is seen as such a normal practice, that “medical professionals totally undermine it,” when mothers struggle to breastfeed. While the support networks are available in the form of health professionals visiting you at home after birth, local drop-in centres, and family and friends — this support is often not enough. Morris stresses the importance of having active support networks, but sometimes having “all the support in the world and it just doesn’t work." Women need to be wholly supported when they face lactation issues.

Many difficulties can be experienced by the mother affecting her ability to breastfeed, including, obesity, C-sections, being an older first-time mum, being sick etc.

Dr Mandy Belfort, an author of a 2013 Harvard study on improved intelligence on breastfeeding, says for some women, their bodies cannot produce enough milk, resulting in guilt and grieving because they are unable to provide sufficient food for their newborn. These insecurities can evolve further into mental health issues and stressors, resulting in the disempowerment of women’s ability to nurse their young.

Whether a woman decides to pump, bottle-feed or mix them both, she should not be stigmatised for making either choice. Instead, we need to be aware of all the issues mothers face and understand them, ultimately empowering women to confidently make the right choices in how they wish to feed their baby.